PRESENTED AS PART OF THE FAN STUDIES NETWORK AUSTRALASIA CONFERENCE 2019

ABSTRACT

What are the tools and techniques required to become a creator of content? This presentation outlines a forthcoming series of workshops that utilises autobiographical experience as a seed for narrative and illustrative practices. The workshops will be conducted in partnership with a Melbourne-based health organisation.

Participants in the initial workshop groups will include adults taking part in Alcohol and Other Drug Programs, as well as both adult and youth participants suffering from mental health issues, more broadly. Participants will gain tools and techniques for plotting their own multi-faceted narratives. Through the iterative workshop model, participants will recognise their role as both collectors and (re)inventors: “storying” the past, acting as creators rather than consumers of their personal stories.

Workshop participants will work with remembered events, writing and drawing from multiple perspectives to create a short narrative piece. Through the production of a narrative artefact, workshop participants are encouraged to explore identity as a composite picture, a fractured and shifting plurality. As participants work through cumulative exercises, they reflect on the past from an alternate temporal frame, a different point of view.

Drawing exercises will explore concepts of inner plurality, visualising various states of emotion and identity through automatic drawing practice. Fiction-writing techniques will facilitate processes of ideasthetic imagining, sensing concepts through attention to thought as embodied experience. As a form of embodied cognition, ideasthetic imagining is a generative process, producing narrative ideas by “writing back” to an event in the past. The concepts of Inner Plurality and Ideasthetic Imagining will be delivered via an iterative workshop model. The aim is to produce a narrative artefact that showcases the fractured, pluralistic nature of identity.

Note- This was a joint presentation between Dr. Julia Prendergast and myself. Below are only the slides and information that I presented.

Introduction

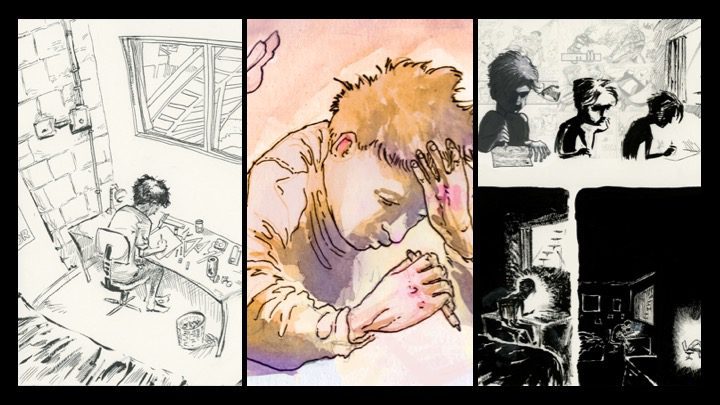

I’m a lifelong doodler, sketcher and maker of comics. Drawing has always been one of the main ways in which I define my identity. Over time though its gone from a place of meditation to one of frustration. The free form play of childhood has become tied up with adult expectations of outputs, over-critical analysis, overbearing fear of failure, and endless competing commitments to the point where my drawing practice often feels like a chore that I need to make time for. I can still get into a state of flow after a while but it’s far from the effortless transition from conscious to unconscious that I experienced when I was young.

I’m interested in identity, and shifting, plural identity states. During my doctorate I made autobiographical comics and I noticed great benefits to my mental wellbeing from creating stories from my past. I became interested in the different characters that I inhabited and that inhabited me over time, and how they all had parts to play, narratives to play out, and cyclical roles to take on. I’ve been trying to use this knowledge to tease out my child-like connection to drawing, to allow the child within me to come out once more, and to help students and non-practicing adults to do the same.

What makes an Artist?

When I was young I drew constantly. It was never a chore, always enjoyable, and there were no blocks to my practice. Over time that has changed, and I feel myself sometimes stifled in my creativity, even questioning myself as a practitioner.

What makes someone a creative practitioner? What are the skills, personality traits, and practices that seperate fans from creators? What makes an artist, and what even is art?

art – noun: art; plural noun: arts; plural noun: the arts

- the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination… producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.

- A skill at doing a specified thing, typically one acquired through practice.

I’m always dubious about the word “artist”. This word highlights misconceptions of an innate, special gift that is out of reach unless you’re lucky enough to be born with it. Ideas like this put up a barrier to initiating arts practice as an adult, when art itself is tied to semi-supernatural conceptions of raw, natural born-talent, out of reach of mere mortals.

Like most people with a form of arts practice, I know that the mystical unicorn of artistic talent actually refers to a broad array of universally achievable traits and practices rooted in the somewhat less mystical foundations of consistency, trial and error, and perseverance. These elements boil down to countless hours of drawing, writing, painting, making music, singing, or whatever it is that passes for talent. There are few shortcuts, and the practice itself is a fundamental requirement towards proficiency in anything, including the creative arts. Consistent practice builds skills over time; such as an eye for design, composition, colour, a sense for poetic structure in prose, or an ear for music.

But what motivates someone to put in the dedicated practice necessary to achieve this illusion of talent? What are the necessary traits and abilities required to spend the time, particularly in the early stages of practice, when skills are undeveloped and outputs are amateurish? While pure stubbornness and grit might be enough; an ability to focus, to enter a state of ‘flow’, and to submerge into the creative process, would seem to be more beneficial and sustainable in the long term. Simply put, if we can derive pleasure through the act of making, regardless of the quality of the thing being made, then the process of putting in time towards proficiency will be made easier- to the point where practice itself is relaxing and fulfilling.

In order to create a space of pleasure and flow in practice, the right mental mindset is key. We can look to a child’s natural affinity for creation and play for inspiration. Children create with an uncritical eye. They enter flow states easily, and don’t hold back from trying new things due to self-imposed restraints.

Automatic Drawing

Automatism refers in general to a complex sequence of behaviour carried out in the almost complete absence of conscious awareness. The concept originated in the context of nineteenth century psychopathology, and often referred to actions carried out under the influence of hypnotic suggestion or to fugues or escapist episodes of which the normal personality had no recollection. It is not ‘stream of consciousness’ but rather a way of tapping into the unconscious mind.

By symbolizing the break with Dadaism around 1920, automatism announced a fresh beginning, a new project. ‘[A]t that moment we lived in a state of euphoria,’ Breton later recalled, ‘almost in the intoxication of discovery. We felt like miners who had just struck the mother lode.’ (quoted in Polizzotti, 1993: 43–4).

Surrealists believed automatic writing provided enhanced access to the imagination (Bacopolous 2012) while Tim Gula cites the practice being used by Jean Giraud (Moebius), Jack Kirby, and Alex Nino, all masters of their craft. Gula cites Moebus saying “when the mind is relaxed it is at its most creative”.

Through Automatic Drawing “the mind disengaged from all critical pressure and scholarly habits” (Soupault, 1967: 664–5) which is the aim of these initial workshops- and in my own practice. Automatic drawing helps ‘break the ice’ and dirty up the intimidating clean white paper.

At a certain point many people lose the ability to enter flow states of creative play. What are the reasons for this? Is it the outcome and achievement focused mindset, instilled through traditional education and assessment? Is it a fundamental neurological change as a function of evolutionary necessity? Or are the reasons mundane and more to do with shifting priorities and interests over time?

Whatever the reasons, the benefits of maintaining an art practice are varied and consistently validated by research. Whether for general well-being, as medicine in the areas of mental health, or as facilitators of social change, art practice is good for individuals, their social and familial circle, and societies more broadly.

Unfortunately, the creation of arts experiences for adults can be challenged when a commonly held narrative is “I can’t draw”. The critical modes of thinking and analysis we build over time ensures that the less competent we feel, the less likely we are to continue. Therefore, it is important to introduce drawing to adults in a way that facilitates a sense of engagement and play, bypassing their assessment and outcome modes of thinking. In the coming workshops I will introduce a process of Surrealist automatism, or automatic drawing, in the hopes of achieving this.

I hope that introducing drawing practice using automatic drawing will take the focus away from the expectations of outcome and onto the joy of the process itself, a necessary element in setting up a practice that will continue into the future.

Automatic Drawing Exercises

- 2 pencil simultaneous drawing, making abstract lines

- Look at lines, start to bring out some lines, look for natural energies

- A natural process, looking for shapes/characters/designs to emerge

- Allowing the drawing to form with minimal conscious input

- Play and the joy of drawing is important- removing stress of worrying about outcome

- ‘Sensed concepts’ developed in the narrative exercises are expressed using automatic drawing techniques.

- Exercise variations:

- Wet media (Watercolour, ink wash)

- Use as basis for drawing- picking out shapes, creatures, designs

- (requires basic overview of brush/paint/ techniques, interactions, and care including

- wet in wet, wet on dry, flicking/spattering, salt, lightening paint/dabbing, warm and cool

- Group discussion- how does it make you feel? What does it remind you of/your associations

- Archetypes Emotions Identities Selves

Brief Workshop summary

Workshop content will consist of basic tutorials including: an introduction to storytelling and drawing and, in later workshops, more comprehensive instruction focusing narrative devices and approaches to traditional text-based storytelling and graphic narratives. In this way, subsequent workshops will build iteratively upon earlier material.

The mediums for expression include writing and drawing exercises: facilitating the production of an artefact including both text and illustrations. Participants are encouraged to visualise their experience of self, and their perception of self, from a variety of perspectives.

Participants will be equipped with skills to think about their life from a variety of perspectives, using simple technical proficiencies in drawing and writing. This will form a sound skill-base, should participants choose to continue to engage with these art practices in the future.

Participation in this project requires two hours of workshop participation and a 20 (twenty) minute survey for successful completion.

Participants will learn:

- Storytelling techniques in both text-based and graphic narrative forms

- Practical exercises to express their experiences and memories

- How to have their work edited and published

Projected research outputs

Research outcomes will include but are not limited to: conference presentations and peer-reviewed journal articles. Non-traditional research outcomes (NTROs) will include but are not limited to: an exhibition of created works as well as a printed anthology showcasing exemplar outputs. Printed copies of the anthology will be distributed by Access HC and through conference presentations and affiliated events.

———————————————————————————————————–

Appendix

Right brain/Left Brain myth- duality of creation/analysis

The concept of left brain and right brain as clear separations of creativity and logic is a commonly known concept that is also unfortunately a myth, although one based on some truth. For example, in language the left brain deals with words and grammar, while the right brain deals in context and tone. (introduce ideational/textual separations in language studies?)

A study published in 2013 looked at a thousand people in MRI machines and could not detect significant separation between the two halves in different tasks. The brain works together in all things. So if the analytical mind is always working, it is necessary to give it something to do besides critical judgment. It needs to be operating from a non-judgemental point of view, looking for patterns, assessing space between marks on the page- developing the design and composition sense that will allow for improvement in skills and outcomes.

Activities need to be designed that incorporate both exploratory/holistic as well as analytical/detail focused mark making.

Autoethnography

The framework of autoethnography analyses an individual’s practices and traditions in a specific field, and belongs to a field of reflective research and variations in definition and terminology including auto-anthropology, autobiographical sociology, self-narrative, and autofictography, among many others. This underscores the possibilities of using personal experience and practices as a basis for research and writing.

Analytic Autoethnography

Both Julia and I are established practitioners within our fields and “Analytic Autoethnographers” (Anderson 2006 p373) ((refers to research in which the researcher is (1) a full member in the research group or setting, (2) visible as such a member in published texts, and (3) committed to developing theoretical understandings of broader social phenomena. As practitioners operating in an academic context, we are familiar with the necessity to balance creative pursuit with contextualisation, justification, and analysis. We are required to keep both aspects of our mind developed- both the exploratory/process-based and the outcome/analysis-based.

Evocative autoethnography

subjectivity, emotional authenticity, personal experience

Carolyn Ellis and Arthur Bochner (2000, 744) further explain that in evocative autoethnography, “the mode of storytelling is akin to the novel or biography and thus fractures the boundaries that normally separate social science from literature . . . the narrative text refuses to abstract and explain.” Evocative autoethnographers have argued that narrative fidelity to and compelling description of subjective emotional experiences create an emotional resonance with the reader that is the key goal of their scholarship. (Anderson 2006 p377)

Evocative auto-ethnography shares traits with aesthetic analysis (the text/work stands alone) and opposite to Rhetoric (using language to explain/rationalise/justify).

Automatic Drawing

In the spring of 1919, the medical student-turned-poet André Breton (1896–1966) and his friend Philippe Soupault (1897–1990) composed ‘the first purely Surrealist work’ (Breton, 1924/1972:35). The product of two wandering minds on paper, Les Champs magnétiques (Breton and

Soupault, 1920/1971) represents the first systematic use of automatic writing by members of the French Surrealist group. Locked in a room for weeks, the two artists let their minds and pens flow freely, generating a written stream evoking the creations of an entranced mind: king dogs, red songs, dead rail stations (Bacopoulous 2012)

Automatism refers in general to a complex sequence of behaviour carried out in the almost complete absence of conscious awareness. The concept originated in the context of nineteenth century psychopathology, and often referred to actions carried out under the influence of hypnotic suggestion or to fugues or escapist episodes of which the normal personality had no recollection. In Pierre Janet’s work L’Automatisme psychologique (1889), there is a distinction between total and partial automatism: in the latter, a part of the mind is split from conscious awareness but still accessible

Looking at two ends of a spectrum- which we can refer to as unity and disintegration, with late nineteenth century philosophers seeing the former as ‘psychological strength’, the latter as ‘weakness’ (Bacopolous 2012)

The ritual importance of the Surrealists’ initiatory experiment with automatic writing is not to be underestimated. Derived from the language of madness and made into one of exaltation, this method opened new literary paths. (Bacopolous 2012 p269)

ARTS AND HEALTH PRACTICE FRAMEWORK

What is arts and health?

Arts and health refers broadly to the practice of applying creative, participatory or receptive arts interventions to health problems and health promoting settings. These arts and cultural interventions have a role across the full spectrum of health practice; from primary prevention through to tertiary treatment.

Or more simply, arts and health can be defined as:

Creating arts and health experiences to improve community and individual health and wellbeing.

Benefits of art practice

- Improved communication skills of people suffering mental health issues (Staricoff, 2004, p. 8).

- Enhanced sense of wellbeing (Geloa, Klassenb, & Gracelya, 2013; Stacey & Stickley, 2010

- Involvement in art can facilitate the process of recovery through positive community experiences (Sapouna & Pamer, 2016)

- This positive relationship between community-based art projects and well-being can “… help provide social and psychological support to family carers of people with mental-health problems” (Roberts, Camic, & Springham, 2011, p. 155).

- The construction of a positive identity is regarded as an important component of wellbeing (Goldie, 2007) and the role of art as a mediator has been linked to positive identity construction (Spencea & Gwinnerb, 2014).

- At a state level, in Victoria, the Art for Health program highlighted the potential for art to have an impact on public attitudes particularly where “… self-image and community perception of participants is often damaged or precarious” (VicHealth, 2002, p. 30)

Indeed, in 2013, the Standing Council on Health and the Meeting of Cultural Ministers endorsed the National Arts and Health Framework. This framework has been developed to enhance the profile of arts and health in Australia and to promote greater integration of arts and health practice and approaches into health promotion, services, settings and facilities.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. (2006). Analytic Autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605280449

Blomdahl, C., Gunnarsson, A. B., Guregård, S., & Björklund, A. (2013). A realist review of art therapy for clients with depression. Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(3), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2013.05.009

Geloa, F., Klassenb, A., & Gracelya, E. (2013). Patient use of images of artworks to promote conversation and enhance coping with hospitalization. Arts and Health, 7, 42–53. doi:10.1080/17533015.2014.961492

Harris, M. W., Barnett, T., & Bridgman, H. (2018). Rural Art Roadshow: a travelling art exhibition to promote mental health in rural and remote communities. Arts and Health, 10(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2016.1262880

Roberts, S., Camic, P. M., & Springham, N. (2011). New roles for art galleries: Art-viewing as a community intervention for family carers of people with mental health problems. Arts and Health, 3, 146–159. doi:10.1080/17533015.2011.561360

Sapouna, L., & Pamer, E. (2016). The transformative potential of the arts in mental health recovery – An Irish research project. Arts and Health, 8, 1–12. doi:10.1080/17533015.2014.957329

Spencea, R., & Gwinnerb, K. (2014). Insider comes out: An artist’s inquiry and narrative about the relationship of art and mental health. Arts and Health, 6, 254–265. doi:10.1080/17533015.2014.897959

Stacey, G., & Stickley, T. (2010). The meaning of art to people who use mental health services. Perspectives in Public Health, 130, 70–77. doi:10.1177/1466424008094811

Staricoff, R. (2004). Arts in health: A review of the medical literature. Retrieved from http://www.artsandhealth.ie/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/AHReview-of-Medical-Literature1.pdf

VicHealth. (2002). Creative connections: Promoting health & wellbeing through community arts participation. Retrieved from https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media-and-resources/publications/ creative-connections