After writing and researching the paper ‘Graphic Storytelling: Teaching Experience and Utility’ (now published and available to read here- https://www.closure.uni-kiel.de/closure8/fisher), I wanted to share it with a general audience. Submitting a pitch to the Australian website The Conversation, I was lucky enough to be paired with Senior editor Sunada Creagh. The article came together nicely and was published with the title, Have you fallen for the myth of ‘I can’t draw’? Do it anyway, and reap the rewards.

It was amazing to see this strike a chord with people. It garnered over 100 comments on the article, past 50K reads, more than 200 shares on The Conversation’s Facebook, interaction on Twitter, LinkedIn, and the other usual suspects. I’m pretty sure it’s not because of the brilliance of my writing in the article. Instead, people connected with the theme of ‘I can’t draw’. There’s an public appetite for further exploration in this area.

I had less than one week to submit something that would distil over 3 thousand words into 800, from an academic audience to a general one. It turned out to be a pretty handy process, on reflection. I was forced to focus on the main takeaways from the research and continually redraft until I could get under the word count. This, while delivering the central ideas in an easy to read and engaging way. My editor was terrific in adding the tweaks that smoothed it all out, creating seamless connections between my sometimes fragmented ideas.

It was such a treat to have this forum to share my views and research on drawing. You can read the article here. Let me know if this resonated with you at all, if it gave you a push to try drawing again, or if it gave you a new angle on drawing as someone who already practices regularly.

Have you fallen for the myth of ‘I can’t draw’? Do it anyway – and reap the rewards

This article is part of a series in The Conversation explaining how readers can learn the skills to take part in activities that academics love doing as part of their work.

Drawing is a powerful tool of communication. It helps build self-understanding and can boost mental health.

But our current focus on productivity, outcomes and “talent” has us thinking about it the wrong way. Too many believe the mythof “I can’t draw”, when in fact it’s a skill built through practice.

Dedicated practice is hard, however, if you’re constantly asking yourself: “What’s the point of drawing?”

As I argue in a new paper in Closure E-Journal for Comic Studies, we need to reframe our concept of what it means to draw, and why we should do it – especially if you think you can’t.

Devoting a little time to drawing each day may make you happier, more employable and sustainably productive.

The many benefits of drawing

I’m a keen doodler who turned a hobby into a PhD and then a career. I’ve taught all ages at universities, in library workshops and online. In that time, I’ve noticed many people do not recognise their own potential as a visual artist; self-imposed limitations are common.

That’s partly because, over time, drawing as a skill set has been devalued. A 2020 poll ranked artist as the top non-essential job.

But new jobs are emerging all the time for visual thinkers who can translate complex information into easily understood visuals.

Big companies hire comic creators to document corporate meetings visually, so participants can track the flow of ideas in real time. Cartoonists are paid to draft innovative, visual contracts for law firms.

Perhaps you were told as a child to stop doodling and get back to work. While drawing is often quiet and introspective, it’s certainly not a “waste of time”. On the contrary, it has significant mental health benefits and should be cultivated in children and adults alike.

How we feel influences how we draw. Likewise, engaging with drawing affects how we feel; it can help us understand and process our inner world.

Art-making can reduce anxiety, elevate mood, improve quality of life and promote general creativity. Art therapy has even been linked to reduced symptoms of distress and higher quality of life for cancer patients.

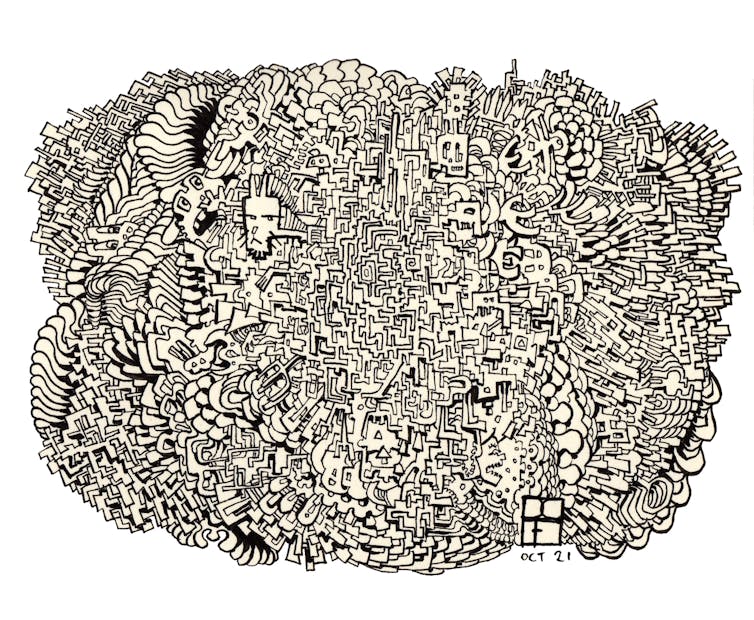

And it can help you enter a “flow state”, where self-consciousness disappears, focus sharpens, work comes easily to you and mental blockages seem to evaporate.

Cultivating a drawing habit

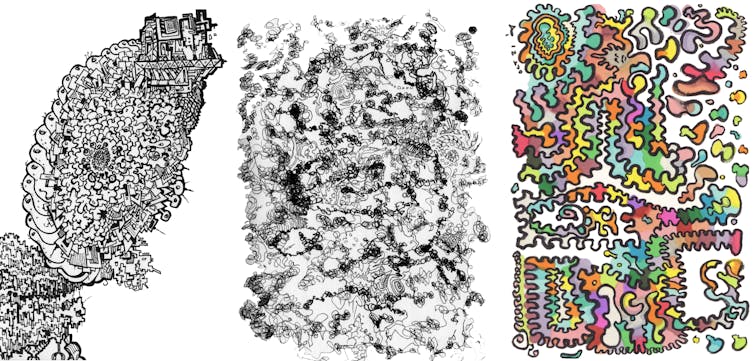

Cultivating a drawing habit means letting go of biases against drawing and against copying others to learn technique. Resisting the urge to critically compare your work to others’ is also important.

Most children don’t care about what’s considered “essential” to a functioning society. They draw instinctively and freely.

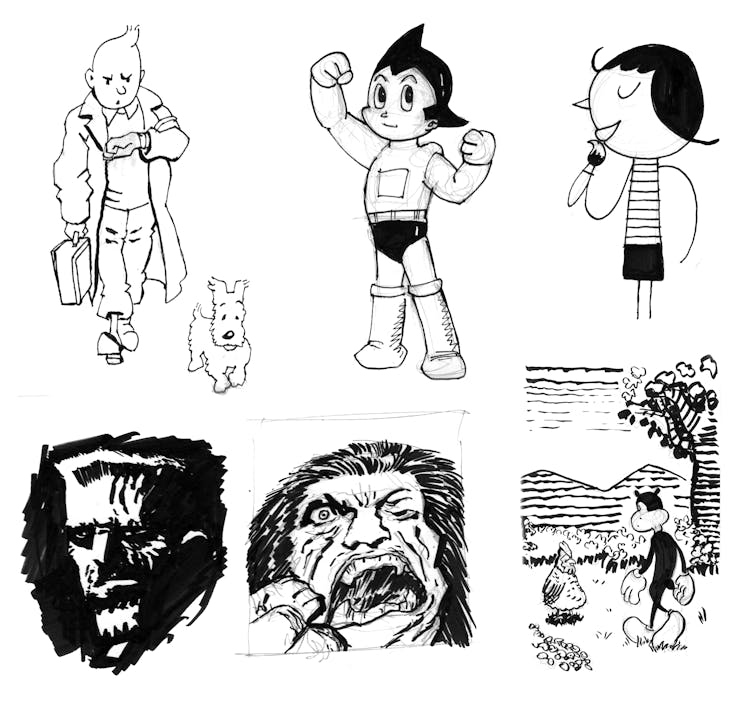

Part of the reason drawing rates are thought to be higher in Japanis their immersion in Manga (Japanese comics), a broadly popular and culturally important medium.

Another is an emphasis on diligent practice. Children copy and practise the Manga style, providing a critical stepping stone from free scribbling to controlled representation. Copying is not seen as a no-no; it’s integral to building skill.

As researcher and artist Neil Cohn argues, learning to draw is similar to (and as crucial as) learning language, a skill built through exposure and practice:

Yet, unlike language, we consider it normal for people not to learn to draw, and consider those who do to be exceptional […] Without sufficient practice and exposure to an external system, a basic system persists despite arguably impoverished developmental conditions.

So choose an art style you love and copy it. Encourage children to while away hours drawing. Don’t worry about how it turns out. Prioritise the conscious experience of drawing over the result.

With regular practice, you may find yourself occasionally melting into states of “flow”, becoming wholly absorbed. A small, regular pocket of time to temporarily escape the busy world and enter a flow state via drawing may help you in other parts of your life.

How to get started

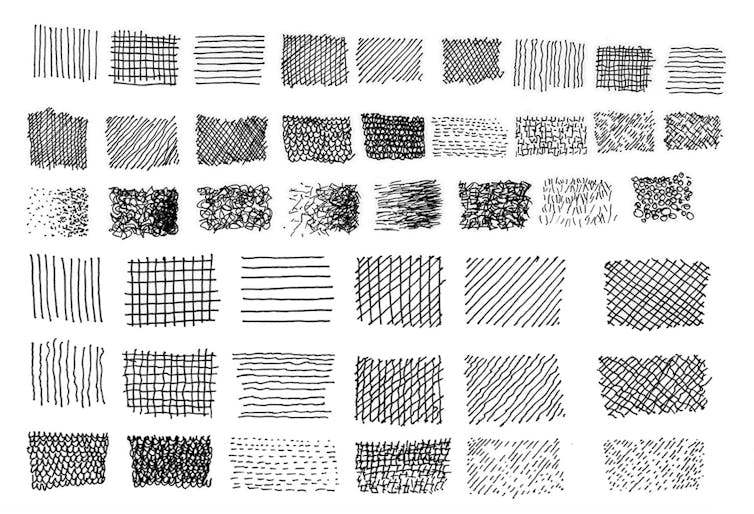

Use simple tools that you’re comfortable with, whether it’s a ballpoint pen on post-it notes, pencil on paper, a dirty window, or a foggy mirror.

Times you’d typically be aimlessly scrolling on your phone are prime candidates for a quick sketch. Doodle when you’re on the phone, watching a movie, bored in a waiting room.

Together with mindful doodling, drawing from observation and memory form a holy trinity of sustainable proficiency.

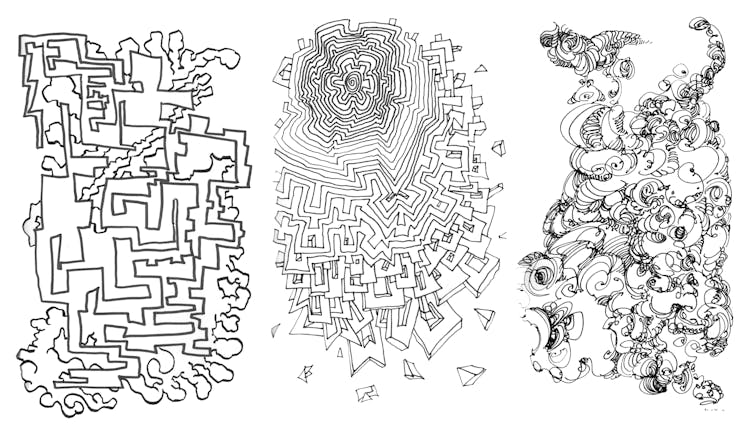

Drawing from life strengthens your understanding of space and form. Copying other styles gives you a shortcut to new “visual libraries”. Drawing from memory merges the free play of doodling with the mental libraries developed through observation, bringing imagined worlds to life.

With time and persistence, you may find yourself producing drawings you’re proud of.

At that point, you can ask yourself: what other self-limiting beliefs are holding me back?